“My approach to design and illustration, my muse, is something that sits in my living room,” explains Magnus Voll Mathiassen, when I ask about the predominant influences that inform his work. “It is a huge, newly-found teak bowl, nothing too special about it. Curved, like the shape of a kidney, it's dark with a few brown wood nuances. This bowl has become my manifesto. It represents—visually and conceptually—what I strive to recreate. I want the function of my work to be obvious, to not be too attention seeking. It should have a sense of timelessness, which is seen in such functional objects, but with small twists that give it character. That encapsulates what I strive for.”

Magnus Voll Mathiassen is a man with a lot to say for himself—one of those rare interviewees who requests more and more questions, more opportunities to explain his practise. Self-effacing and introspective, he’s aware that his audience sometimes needs assistance translating the distinctive and personal visual language that has become his trademark. He’s also clearly relishing the opportunity, since founding solo venture The MVM, to speak both visually and verbally in a voice that’s entirely his own.

It hasn’t always been this way for the Norwegian designer. Until 2009, Mathiassen contributed instead to the collective voice of Grandpeople, the design practise he co-founded in 2005 with college friends Christian Strand Bergheim and Magnus Helgesen. Based in Bergen, a city on Norway’s western coast with its own flourishing creative community, Grandpeople swiftly ascended to the upper echelons of the hip Scandinavian design scene; their colourful, organically-abstracted designs and deeply-embedded pop-culture references were a near-instant hit with the international design press (indeed, they graced Grafik’s profile pages mere months after their official formation). After four years, they seemed to all extents and purposes to have made it—but it was at this point that Mathiassen made the decision to go solo.

“I have these three-year cycles,” Mathiassen explains, when quizzed on the motivations for his departure. “I’ve had it since I was a kid. I gradually get bored. When I look back, everything I’ve done in my life has only lasted for three years. So, my four years in Grandpeople was one year too many.” That three-year itch wasn’t his only motivation for leaving both Grandpeople and Bergen behind, however. “When you are part of a studio with more than yourself to think about, and when the studio's work gets some sort of recognition, your ideas and your inner forces need to some extent be tamed,” Mathiassen reflects. “For me, being a part of a voice that wasn’t mine alone, it was tearing me apart a bit.”

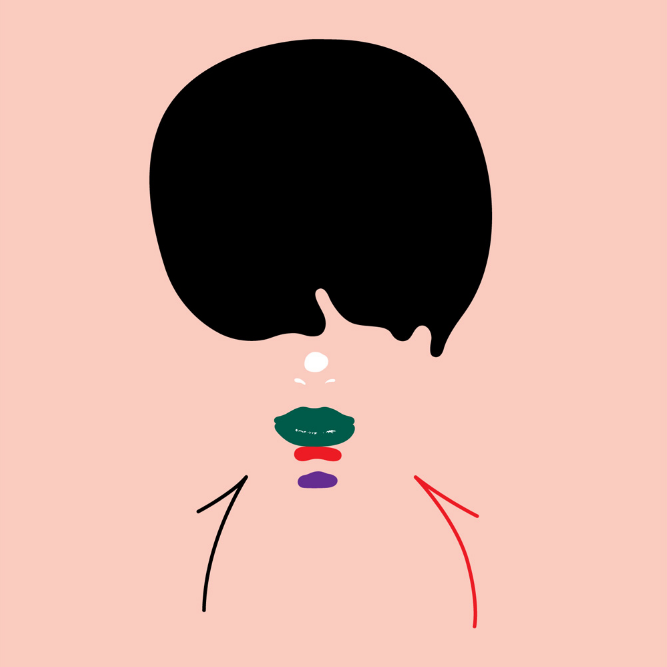

This need for independence - coupled with Bergen’s constant bad weather - drove him to return to the gentler climate and slower pace of Drammen, the small industrial town in which he grew up. It was here, in isolation from the creative community in which he’d first made his name, that Mathiassen set up solo as The MVM. Since doing so, he’s carved himself a singular niche with his peculiar, concept-driven imagery. Working under the self-designated banner of “research-led design”, The MVM applies a sensitive, cerebral approach to illustration, typography and graphics, connecting aesthetic elements and ideas in enigmatic ways and translating concepts into images that are at once complex and minimalist. It’s a stripped-bare way of working that Mathiassen has developed through a process of rigorous introspection and extensive reading, which seems a direct consequence of his conscious decision to disengage from the less savoury trappings of the creative community.

It’s clear from Mathiassen’s responses on this score that his relationship with the creative industry is volatile at best. “Seeing all the social media, the blogs, the bad advertising, the zeitgeists and what have you – it can make you dizzy, alienated and cold-hearted.” He explains. “One year ago I was about to give up this industry. I was fed up with all things around me that seemed to be products made by people who lacked a personal standpoint or agenda. I had to take a break from it all. So I stopped reading magazines, barely checked any websites, and so on and so forth. Instead, I read a lot, and got focused, and that isolation was healthy for me. Now, I don’t spend too much time watching everybody else pick their noses – I need to find my treasure other places. And I know I am not here to please people. I am here to do my best work.”

Ironically, this act of enforced isolation seems only to have served to prove that, for Mathiassen at least, those two activities need not be mutually exclusive; for someone who claims to be so oblivious to the goings-on in the industry around him, he’s certainly managed to capture a facet of the zeitgeist with his meticulously-researched work since setting up The MVM. Mere months after the inception of his solo practise, that he was chosen by a panel of industry experts and editors as one of the twenty-four most promising practitioners in his field at London’s inaugural Pick Me Up art fair, and this was followed by invitations to contribute to the International Poster Festival in the French city of Chaumont, and to the Life In 2050 exhibition in London last summer.

It can’t be denied that Mathiassen’s rapid ascent to both commercial independence and critical recognition mirrors that of Grandpeople six years ago, and the contacts he forged during his time with them may well have given him something of a leg-up in his solo career. It would be unjust, though, to attribute his successes with The MVM solely to the skills and reputation he gained with Grandpeople. This time around, he’s achieved it on his own terms, ploughing his energy into projects that he finds personally fulfilling, and always looking to the future. “I seldom look back at my body of work,” he reveals. “I work because I have to work. If I chose something to be a favourite project, I’d end up comparing it to everything I did in the future. I already have a tendency to never be entirely satisfied with my work, and that makes me work harder. It’s an evil spiral for me, but a good one for the people I work for.”

Evil it might be, but it’s this perfectionist attitude that’s allowed Mathiassen to strike that sought-for balance between projects for small clients who share his personal ideology, such as independent record labels Rune Gramofon and The Last Record Company, and the big, high-profile commissions from the likes of Nike that pay the bills. They all get the same, near-obsessive fine-tuning from The MVM, the same rigorous developmental processes that result in the minimalist quality evident in much of his imagemaking. He’s characteristically self-effacing even about this side of his work, explaining “I have a terribly bad memory, which affects every aspect of my life. I am probably not the only one with this problem. As a result, I make work that’s stripped down to the bare essentials – so people will remember it. But it is hard. More is more, and less is hard. Making it look easy is harder.”

The inevitable question now, as another of his three-year cycles draws to a close, is what next? He hints, more than once, at a desire for the freedom – if not the trappings – of the art world, but is quick to dismiss it as a serious ambition. “I see a lot of work around created with an intention to be autonomous as well as referential. Design and illustration made as art, or at least trying to be,” he says. “These projects often collapse conceptually. There are a few examples that manage to function on multiple levels, and I admire people for being able to do this. But I don’t work like this. I work in a business where money controls the direction of my work, and the outcomes will never be fully my own. But by working with aesthetics in a utopian way, I can create a conceptual foundation to my work which is personal, and which is my own. Each piece I create is important, but the full body of work is to me more important, and more interesting.”

Perhaps the most valuable freedom that The MVM has given Mathiassen is the scope to create a body of work that satisfies him personally as well as commercially, and the ability to tailor his practise, over time, to pursue the kind of work that leaves him feeling most creatively and intellectually fulfilled. And as for his own perspective on the future? “The important thing now is to gradually shift direction, and always be relevant, especially to myself. Otherwise, I'll be forced to start fresh again. And that seems like bad business.”

Originally published in Grafik magazine, issue 189. Images © Magnus Voll Mathiassen.